A Sophisticated Treatise on Communication

An illustrated reflection on Jane Austen’s Emma1

I frequently wanted to strangle the title-character of Jane Austen’s novel, Emma, or at least shake her out of her self‐absorbed, self‐infatuated bubble. I even had to clap the book shut on several occasions in acutely embarrassed empathy when she seemed to be careening—once again—towards certain social or romantic disaster.

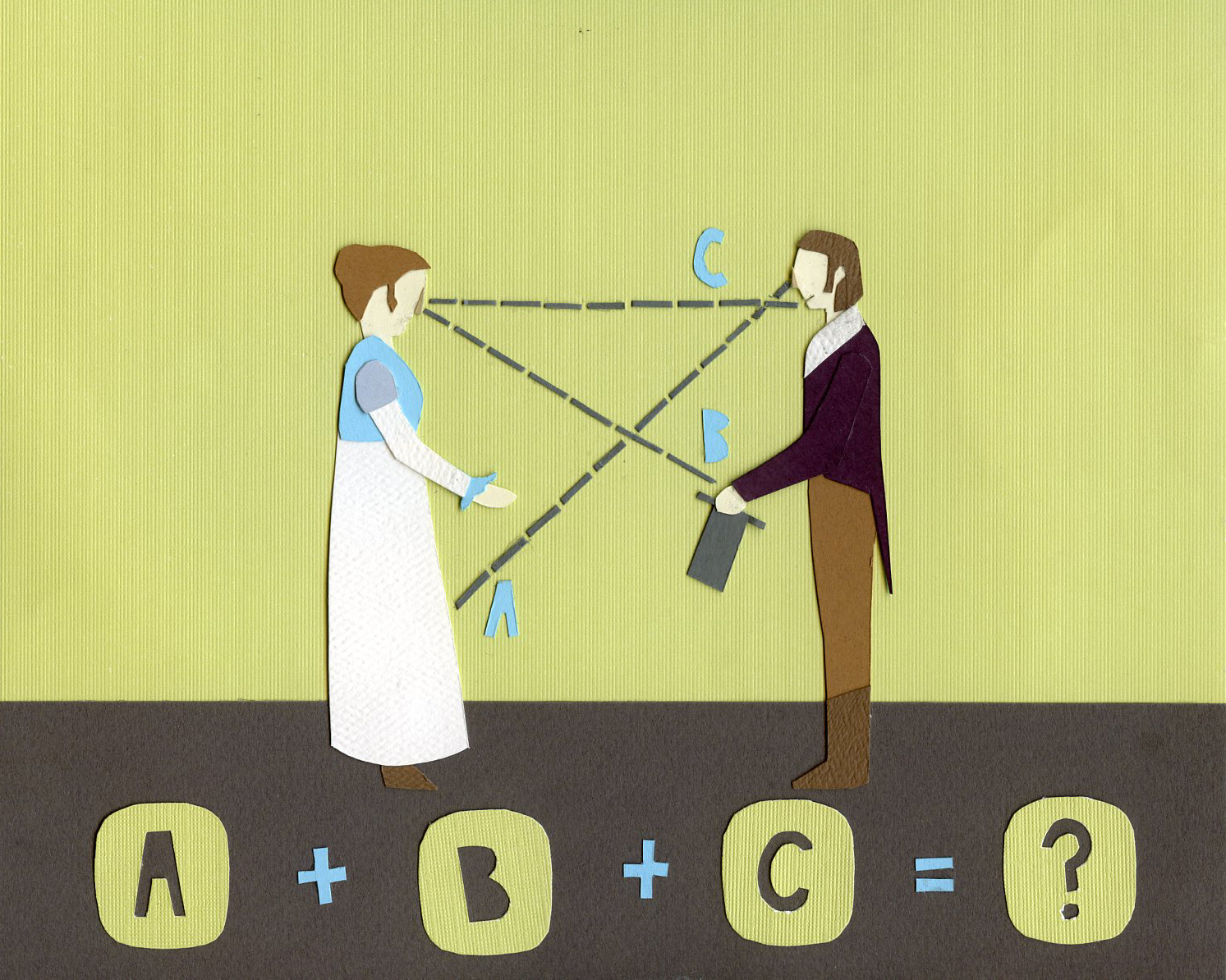

However, Emma the character (and the book) becomes infinitely more palatable when one considers the novel as a study in manners and as a primer on all the ways we can mistakenly or willfully misunderstand each other. It is more than a love story, it is a sophisticated treatise on communication.

In the small village of Highbury, so much depends on a single glance, a raised eyebrow, a hand held overlong or an unexpected note in a voice. Readers follow Emma as she navigates, with varying degrees of success, the small and subtle signals that underlie spoken conversation. In the novel, the spoken and the unspoken often contradict each other entirely: “With such sensations, Mr. Elton’s civilities were dreadfully ill-timed; but she had the comfort of appearing very polite, while feeling very cross.”

Those who succeed in society are those who can read and react appropriately to these unspoken cues—a skill no less valuable today, than in the Austen’s England. Misinterpretation and disingenuousness are strong motifs throughout the novel: “He had misinterpreted the feelings which had kept her face averted and her tongue motionless,” and “Emma denied none of it aloud, and agreed to none of it in private.”

Emma’s social education throws her in the way of Frank Churchill, a stylish young man who may not be whom he appears, Harriet Smith, an orphan whose guileless eyes and mind take everything as literal, and Jane Fairfax, whose reserve and elegance shield her real feelings from the world. Throughout her adventures and misadventures, Emma’s constant companion is Mr. Knightley, a long‐time friend of the family, whose solid good‐sense provokes and inspires Emma to improve herself. Though self‐absorbed and entitled, Emma does have one great virtue: she sincerely wants to improve herself. Haven’t we all been there and longed for someone to cut us a little slack? We are trying, after all.

The characters in Austen’s Emma meet around card tables and send each other little notes through the local post. Though the technologies that mediate so many of our relationships today—Facebook, Twitter, OKCupid, AIM—claim to make it easier to communicate with friends near and far, the opportunities for misunderstanding have only increased. So like Emma, we sift through what see and hear and read, and pray that we have the clear eyes to see the world as it is, and not as we want it to be.

As Mr. Knightley declares to Emma, “[One is] always deceived, in fact, by his own wishes, and regardless of little besides his own convenience… My Emma, does not everything serve to prove more and more the beauty of truth and sincerity in all our dealings with each other?”